Reflections of an

Inextricable Bond

Lexie Kite

DEVELOPMENT DIRECTOR

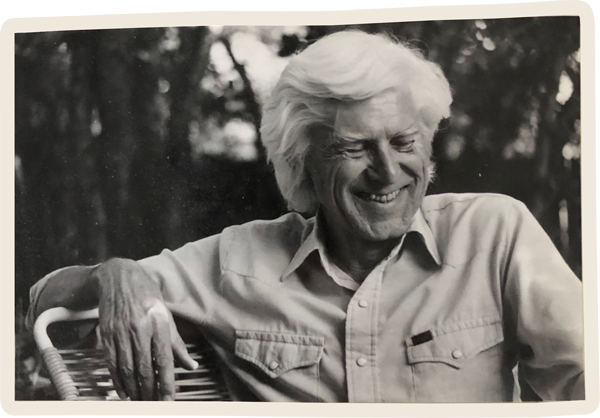

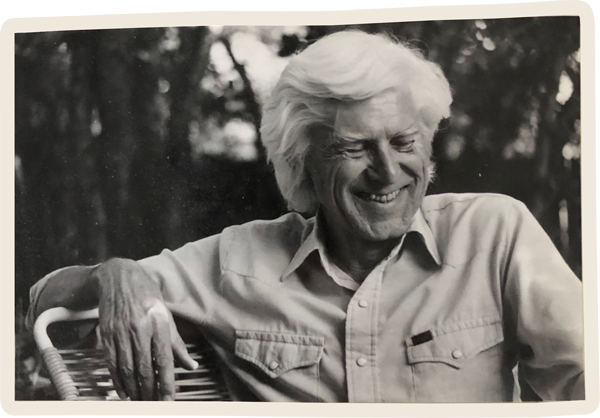

Emeritus Professor Edward Lueders taught at the University of Utah for 24 years where he directed the Creative Writing Program, chaired the Department of English, served as editor of the Western Humanities Review, and published 13 books, ranging from creative nonfiction (including The Clam Lake Papers and The Salt Lake Papers), to collections of modern verse, critical biographies, translations, and beyond. Still active and writing at 98, his new book, Living on This Animal Planet: Zodiac Annual Poems with Papers, is ready for its publisher. On top of all this, he spent 40 years consulting with secondary school students and teachers as Poet in the Schools throughout the U.S., India, and Japan. His honors include a Fellowship in Creative Writing from the National Endowment for the Arts, the 1992

Governor’s Award in the Humanities from Utah Humanities, and the 1998 Entrada Institute Award for Environmental Education. At the end of his career, he was appointed the prestigious honor of University Professor.

His creativity, it should be noted, extends far beyond the written word. He has been playing jazz piano for audiences ever since 1943, when he was drafted into the US Armed Forces as a special services pianist. He has played at Utah ski resorts, including years as house pianist at Alta’s Rustler Lodge. He was the dinner pianist at the Capitol Reef Inn in Torrey, Utah, where he and his wife, Deborah Keniston, built their retirement home, and volunteered as a lobby pianist for the University of Utah Hospital.

◀ Edward Lueders’ The Salt Lake Papers, University of Utah Press, 2018.

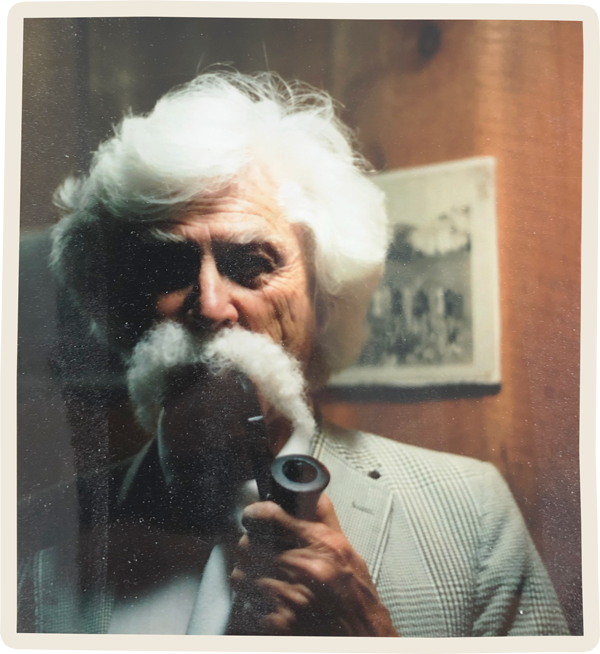

Former students and community members may also remember Lueders and the late English Professor Kenneth Eble traveling throughout Utah performing a two-man show featuring the famed authors Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. In his yet-to-be-published memoir, Lueders reflects on his inextricable bond with Eble, who passed too soon, and their classroom teaching brought to life:

“On the university campus, Ken and I each taught a range of courses. Our overlap was in American Literature. He especially liked to teach a concentrated single-author course on the work of Henry David Thoreau. Once when he was deep in the course, I chided him that he was beginning to look like Henry. In fact in some respects he did. He was short and compact with a largish head and a nose to match. I kidded him that he ought to get himself up as Thoreau and teach his class in the guise of his subject.

I didn’t suppose he’d take me seriously, but, always interested in making teaching techniques more vital, he did. A few days later he told me he’d do it—if I would ‘do’ Ralph Waldo Emerson with him, so that the two worthies, friends associated in

life, could perform a dialogue to be fashioned from their writings. I was teaching a course on the New England Transcendentalists at the time and had always felt an affinity with Emerson. So I went for the idea, borrowed a 19th century frock-coat from the theater department, and played Emerson to his Thoreau.

Ken drafted and I collaborated on a conversational script drawn chiefly from their books and essays. Ken’s costume was modeled on the frequently published drawing of Thoreau in a knee-length coat, floppy hat, heavy shoes, and stout walking stick. To tailor the dialogue for our classes, we devised the script as our responses to an interview conducted by one of our students for whom we had written in the pertinent leading questions. Thoreau, as you might imagine, had all the best lines with Waldo as a kind of witty high-flown straight man. The most popular and challenging part of the skit came at the end with unrehearsed questions from the audience. By then we were steeped in our characters’ language and manner. Our professorial familiarity with our subjects enabled us to ad lib our response faithfully in character.

We performed the skit first for Ken’s Thoreau class. Then we did it for mine. By then The Salt Lake Tribune learned of our act, and we appeared photographed in costume with an accompanying write-up on the first page of the local section. That did it. High schools and colleges in the area began to invite us to perform for their classes. We were pleased to accept. The Utah Humanities Council caught our act and booked us under their aegis in libraries and auditoriums all over the state. Word got around. We were even asked to perform at an educator’s convention in Chicago. Which we did. We were having a high time with the act. But we were teachers, not actors, and it was getting out of hand. I returned the

Emersonian frock coat to the theater costume department, we filed the script with our press clippings, and we went back to our course work and our own writing.

Kenneth Eble died at the height of his career as an outstanding nationally celebrated educator and author. After a hot game of tennis he sensed the signs of heart attack and drove himself to the hospital. There he underwent heart surgery from which he began to rally but then succumbed. Ken was 62. At a grave-side ceremony and again at a campus-wide memorial, Bill Mulder and I read excerpts from Thoreau’s Walden and key passages I had chosen from Ken’s own works. The echoes seemed right.”

Reflections of an

Inextricable Bond

Lexie Kite

DEVELOPMENT DIRECTOR

Emeritus Professor Edward Lueders taught at the University of Utah for 24 years where he directed the Creative Writing Program, chaired the Department of English, served as editor of the Western Humanities Review, and published 13 books, ranging from creative nonfiction (including The Clam Lake Papers and The Salt Lake Papers), to collections of modern verse, critical biographies, translations, and beyond. Still active and writing at 98, his new book, Living on This Animal Planet: Zodiac Annual Poems with Papers, is ready for its publisher. On top of all this, he spent 40 years consulting with secondary school students and teachers as Poet in the Schools throughout the U.S., India, and Japan. His honors include a Fellowship in Creative Writing from the National Endowment for the Arts, the 1992 Governor’s Award in the Humanities from Utah Humanities, and the 1998 Entrada Institute Award for Environmental Education. At the end of his career, he was appointed the prestigious honor of University Professor.

Edward Lueders’ The Salt Lake Papers, University of Utah Press, 2018.

His creativity, it should be noted, extends far beyond the written word. He has been playing jazz piano for audiences ever since 1943, when he was drafted into the US Armed Forces as a special services pianist. He has played at Utah ski resorts, including years as house pianist at Alta’s Rustler Lodge. He was the dinner pianist at the Capitol Reef Inn in Torrey, Utah, where he and his wife, Deborah Keniston, built their retirement home, and volunteered as a lobby pianist for the University of Utah Hospital.

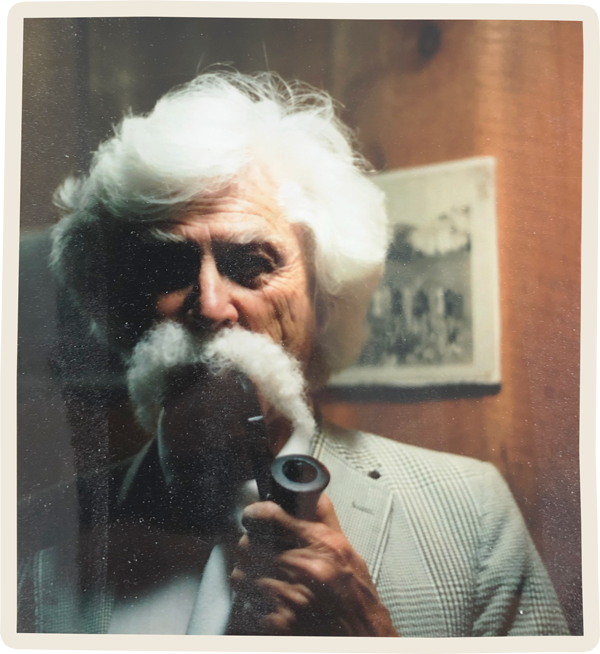

Former students and community members may also remember Lueders and the late English Professor Kenneth Eble traveling throughout Utah performing a two-man show featuring the famed authors Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. In his yet-to-be-published memoir, Lueders reflects on his inextricable bond with Eble, who passed too soon, and their classroom teaching brought to life:

“On the university campus, Ken and I each taught a range of courses. Our overlap was in American Literature. He especially liked to teach a concentrated single-author course on the work of Henry David Thoreau. Once when he was deep in the course, I chided him that he was beginning to look like Henry. In fact in some respects he did. He was short and compact with a largish head and a nose to match. I kidded him that he ought to get himself up as Thoreau and teach his class in the guise of his subject.

I didn’t suppose he’d take me seriously, but, always interested in making teaching techniques more vital, he did. A few days later he told me he’d do it—if I would ‘do’ Ralph Waldo Emerson with him, so that the two worthies, friends associated in life, could perform a dialogue to be fashioned from their writings. I was teaching a course on the New England Transcendentalists at the time and had always felt an affinity with Emerson. So I went for the idea, borrowed a 19th century frock-coat from the theater department, and played Emerson to his Thoreau.

Ken drafted and I collaborated on a conversational script drawn chiefly from their books and essays. Ken’s costume was modeled on the frequently published drawing of Thoreau in a knee-length coat, floppy hat, heavy shoes, and stout walking stick. To tailor the dialogue for our classes, we devised the script as our responses to an interview conducted by one of our students for whom we had written in the pertinent leading questions. Thoreau, as you might imagine, had all the best lines with Waldo as a kind of witty high-flown straight man. The most popular and challenging part of the skit came at the end with unrehearsed questions from the audience. By then we were steeped in our characters’ language and manner. Our professorial familiarity with our subjects enabled us to ad lib our response faithfully in character.

We performed the skit first for Ken’s Thoreau class. Then we did it for mine. By then The Salt Lake Tribune learned of our act, and we appeared photographed in costume with an accompanying write-up on the first page of the local section. That did it. High schools and colleges in the area began to invite us to perform for their classes. We were pleased to accept. The Utah Humanities Council caught our act and booked us under their aegis in libraries and auditoriums all over the state. Word got around. We were even asked to perform at an educator’s convention in Chicago. Which we did. We were having a high time with the act. But we were teachers, not actors, and it was getting out of hand. I returned the Emersonian frock coat to the theater costume department, we filed the script with our press clippings, and we went back to our course work and our own writing.

Kenneth Eble died at the height of his career as an outstanding nationally celebrated educator and author. After a hot game of tennis he sensed the signs of heart attack and drove himself to the hospital. There he underwent heart surgery from which he began to rally but then succumbed. Ken was 62. At a grave-side ceremony and again at a campus-wide memorial, Bill Mulder and I read excerpts from Thoreau’s Walden and key passages I had chosen from Ken’s own works. The echoes seemed right.”